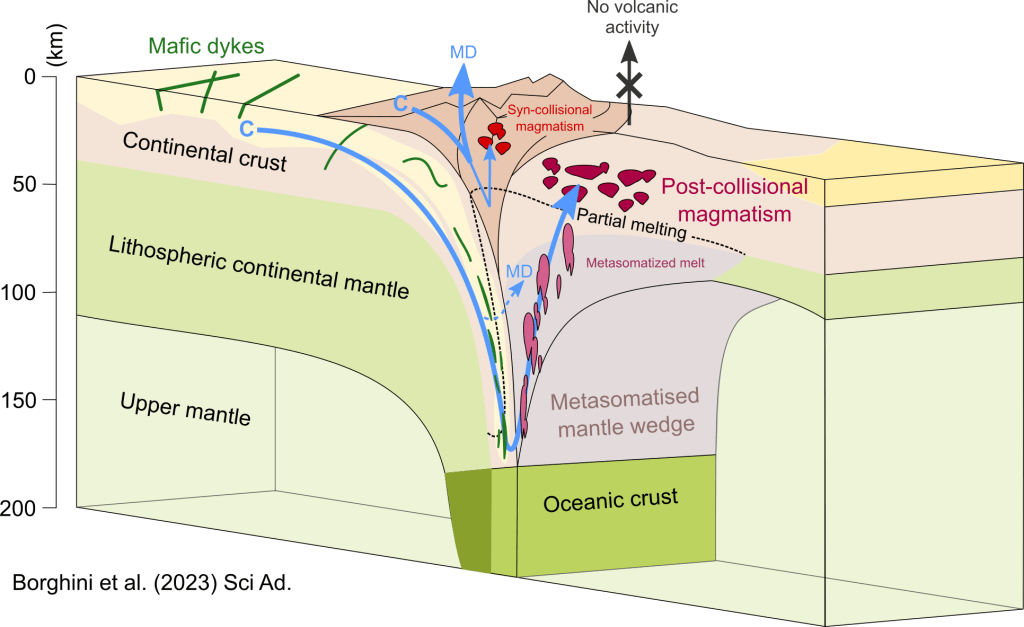

In the modern Earth, plate tectonics allows for the reworking of surface material (i.e. erosion/weathering – burial – partial melting) in active convergent settings. This process mobilises and drags a substantial volume of mineral-bound volatiles (i.e. CO2, H2O) to lower crustal and mantle depths. Most of these volatiles, chief among them carbon, rapidly find their way back to the surface through volcanic activity in subduction zones(Horton, 2021), thus maintaining surface habitability. However, due to its relative stability and longevity, the partially melted metamorphic continental crust can isolate a significant amount of carbon from the atmosphere for protracted periods of time, modulating the carbon cycle over hundred million of years (Nicoli & Ferrero, 2021).

Over the last decade, our understanding of crustal differentiation has markedly improved thanks to the discovery of melt and fluid inclusions in deep crustal lithologies (Bartoli & Cesare, 2020). The landmark study by Cesare et al. (2009) demonstrated that during partial melting of the lower crust, pristine melt can be trapped and preserved as inclusions within newly formed minerals (e.g. garnet) in regionally metamorphosed granulite and high-pressure rocks. Such melt inclusions have commonly crystallised and are composed of an aggregate of micrometric crystals (i.e. nanorocks or nanogranitoids), although glassy inclusions may also be present, and might occur along with fluid inclusions (CO2, CH4, N2, H2O) (Carvalho et al., 2019; 2020). Unlike volcanic glass inclusions in magmatic bodies, they preserve the original melt composition (major, trace element and volatile content) at the time of entrapment at peak metamorphic conditions (Bartoli et al., 2014). Analytical developments, such as the advent of nanoscale and time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry, now permit us to retrieve precise three-dimensional microstructural, chemical and isotopic information at the scale < 100 nm (Ferrero et al., 2021; Parisatto et al., 2018). Hence, these “messages in the bottle” (Clemens, 2018) are invaluable archives, which contain clues for the evolution of the solid Earth.

Our recent studies (Nicoli & Ferrero, 2021; Nicoli et al., 2022; Borghini et al., 20223) have shown that melt inclusions in metamorphic rocks can be used to retrieve information on the carbon content of the supracrustal protolith and constrain the volatile budget of mountain belts. Our new flux estimates for the burial of continental material in Phanerozoic continental collision and continental subduction settings rival those of active volcanoes (Lee et al., 2019), making the continental crust a key player in the evolution of the carbon cycle.

Carbon budget of the deep and ultra-deep crust references

Other references

Bartoli, O., & Cesare, B. (2020). Nanorocks: a 10-year-old story. Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali, 31, 249-257. Bartoli, O., Cesare, B., Remusat, L., Acosta-Vigil, A., & Poli, S. (2014). The H2O content of granite embryos. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 395, 281-290.

Carvalho, B. B., Bartoli, O., Cesare, B., Tacchetto, T., Gianola, O., Ferri, F., … & Szabó, C. (2020). Primary CO2-bearing fluid inclusions in granulitic garnet usually do not survive. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 536, 116170.

Carvalho, B. B., Bartoli, O., Ferri, F., Cesare, B., Ferrero, S., Remusat, L., … & Poli, S. (2019). Anatexis and fluid regime of the deep continental crust: new clues from melt and fluid inclusions in metapelitic migmatites from Ivrea Zone (NW Italy). Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 37(7), 951-975.

Cesare, B., Ferrero, S., Salvioli-Mariani, E., Pedron, D., & Cavallo, A. (2009). “Nanogranite” and glassy inclusions: The anatectic melt in migmatites and granulites. Geology, 37(7), 627-630.

Clemens, J. D. (2009). The message in the bottle:“Melt” inclusions in migmatitic garnets. Geology, 37(7), 671-672.

Ferrero, S., Ague, J. J., O’Brien, P. J., Wunder, B., Remusat, L., Ziemann, M. A., & Axler, J. (2021). High-pressure, halogen-bearing melt preserved in ultrahigh-temperature felsic granulites of the Central Maine Terrane, Connecticut (USA). American Mineralogist: Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials, 106(8), 1225-1236.

Horton, F. (2021). Rapid recycling of subducted sedimentary carbon revealed by Afghanistan carbonatite volcano. Nature Geoscience, 14(7), 508-512.

Lee, C. T. A., Jiang, H., Dasgupta, R., & Torres, M. (2019). A framework for understanding whole-Earth carbon cycling. In Deep Carbon: Past to Present (pp. 313-357). Cambridge University Press.

Parisatto, M., Turina, A., Cruciani, G., Mancini, L., Peruzzo, L., & Cesare, B. (2018). Three-dimensional distribution of primary melt inclusions in garnets by X-ray microtomography. American Mineralogist: Journal of Earth and Planetary Materials, 103(6), 911-926.